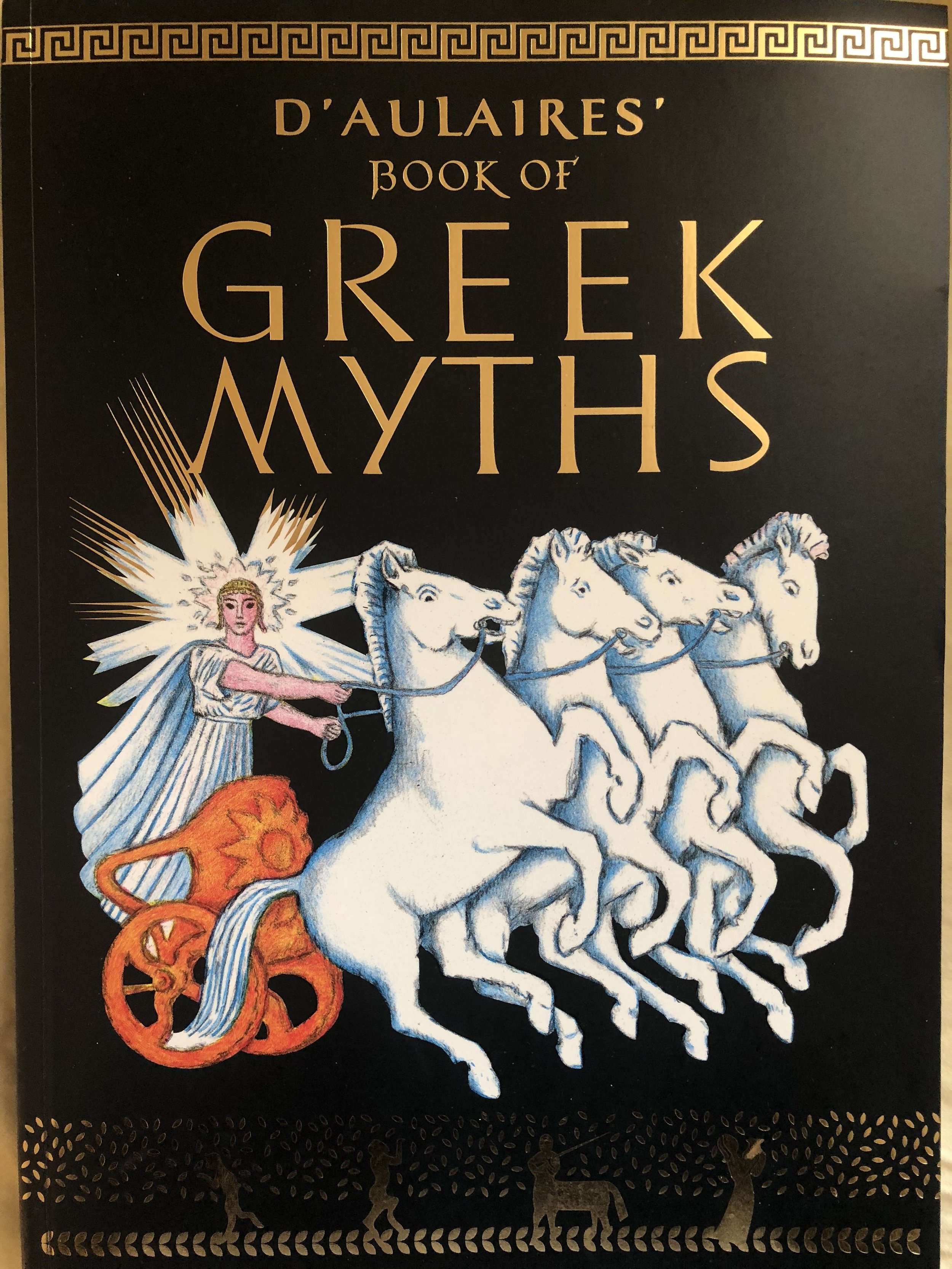

HOUSEHOLD GODS: D'AULAIRES' BOOK OF GREEK MYTHS

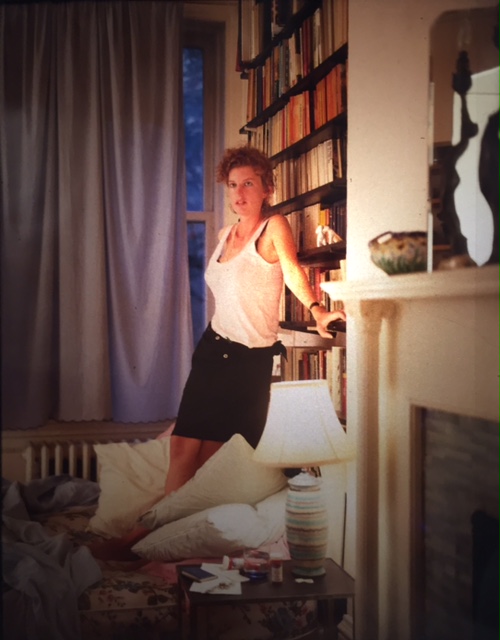

Lisa Zeiger

“The world will treat your children as you have treated them.”--Alice Neel

To reopen, at sixty, the pages of D’Aulaires’ Book of Greek Myths, a children’s book I first read at six, is to uncover my real childhood, the one lived in the house of books, rather than the contemporary house I lived in, often in terror, in the hills of Los Angeles in the 1960s.

My father was Jewish, my mother, Unitarian. I suppose I had a vaguely Christian orientation, imposed by the right-wing, faux-WASP, fancy private school I attended, but I knew the faith preached there was one of hypocrite punishers. It was not until my forties that I was able to shed that trauma, and be baptized into the Episcopal Church.

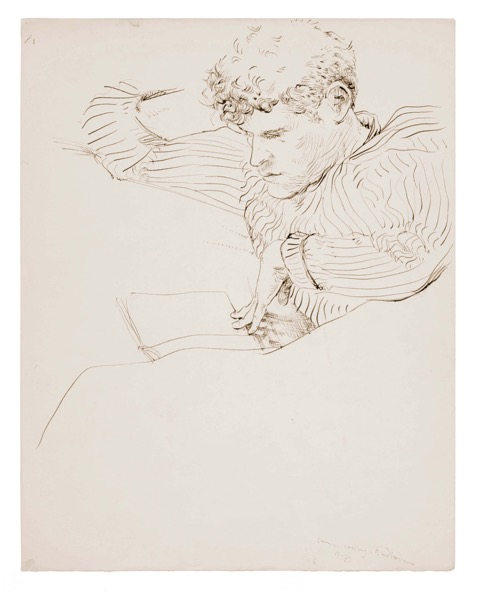

But to this day, D’Aulaires’ Book of Greek Myths, published in 1955 and still in print, is my true catechism. I have never read Homer, or Pindar, or Aeschylus, but from the d’Aulaires--a married couple, who met in 1929 in Munich while studying with the painter Hans Hoffman, and later knew Robert Graves, traveling the Greek islands, sketching and writing-- I know the names and deeds of every Olympian, every one of their offspring, every mortal, every monarch, every hero, every beast, and every monster.

The foibles, powers and beauties of the Greeks still make more sense to me than the protagonists and punishments of the Bible. Certainly, at six, they sheltered me from and explained to me the irrational rage of father, school, and spoilt peers. The displeasure of the gods was always emotionally intelligible, whereas I have never understood God’s rejection of Cain’s offering of his harvest, while exalting Abel’s burnt cattle. An Episcopal priest blithely explained it to me this way: “Perhaps God wanted a ham sandwich that day.” But if God is all-knowing, he knew his favoritism would incite fratricide. I have always sided with Cain, the murderous sower; just as I honor Hagar, the slave who bears Abraham a son, Ishmael--the outcasts--more than I do Sarah, Abraham’s barren wife, who chastises Hagar in jealousy, before, at ninety, giving birth to Abraham’s second son, Isaac. At six, I did not yet know I was illegitimate, but I sensed in myself the scapegoat, the proof of something not quite warded off.

Genealogy of the Gods.

The magnificent illustrations of the d’Aulaires were my initiation into the wonderful counterpoint of word and image that is possible, and which ought to be mandatory in our lives. (Alice in Wonderland was another such experience, and, indeed, another literary shelter, but it was d’Aulaires’ that first gave me an inkling of the divine connection between logos and eikon.)

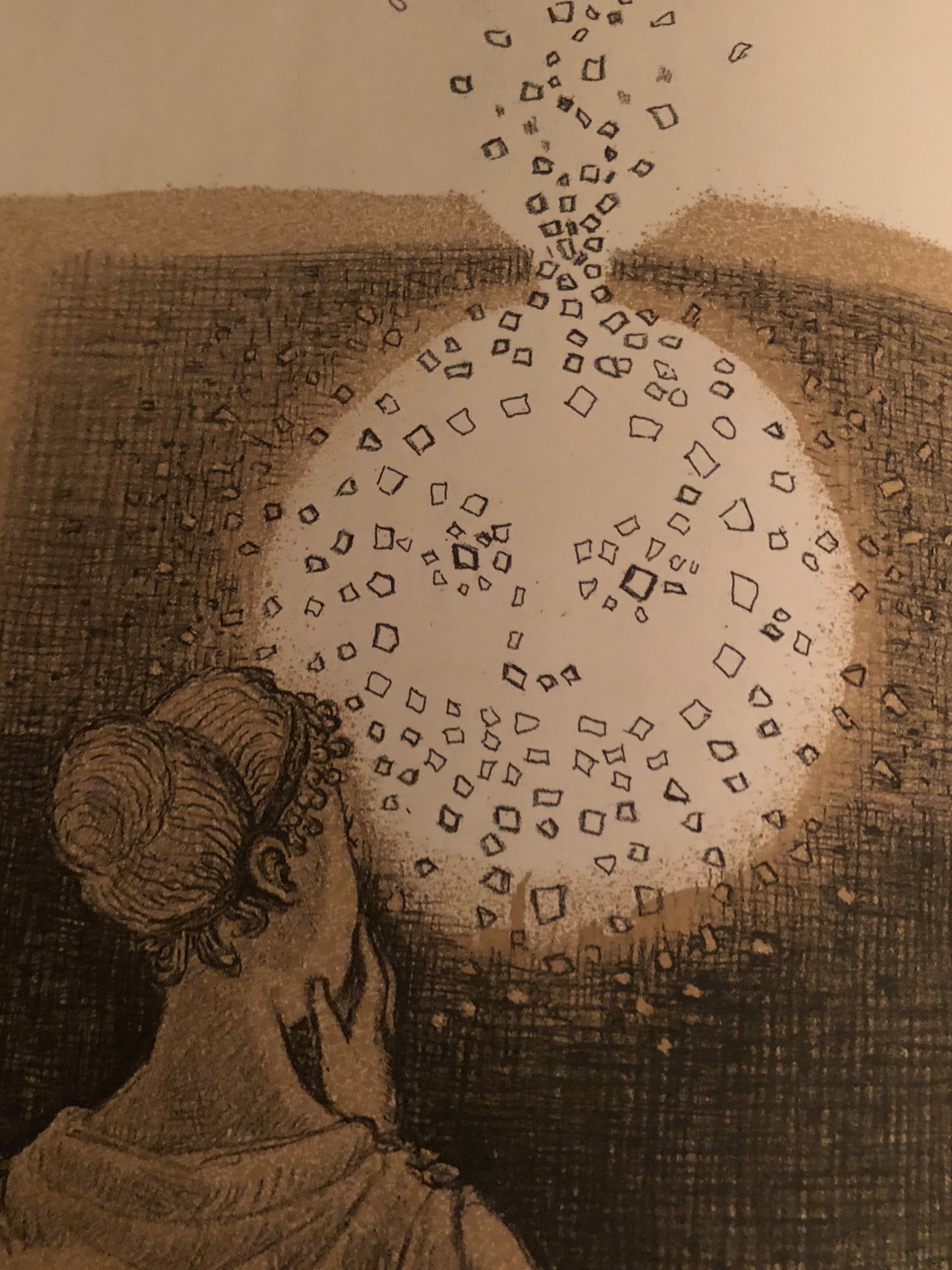

At six, I was unnaturally curious about the gods’ methods of seducing mortals. When I remember the Greek myths, the first I think of is one from the middle of the collection; of the beautiful Danae, immured by her father, King Acrisius, in a sealed room with only an opening in the roof, because an oracle had foretold that his daughter’s son would kill him. “There no suitor could see her beauty and she would remain unwed and childless.” Wily Zeus, however, visits Danae in the form of a shower of gold pieces. Danae gives birth to Perseus; upon discovering the infant and realizing he is the son of Zeus, Acrisius does not kill him, but locks Danae and Perseus in a chest which he casts out to sea. “If they drowned, Poseidon would be to blame.”

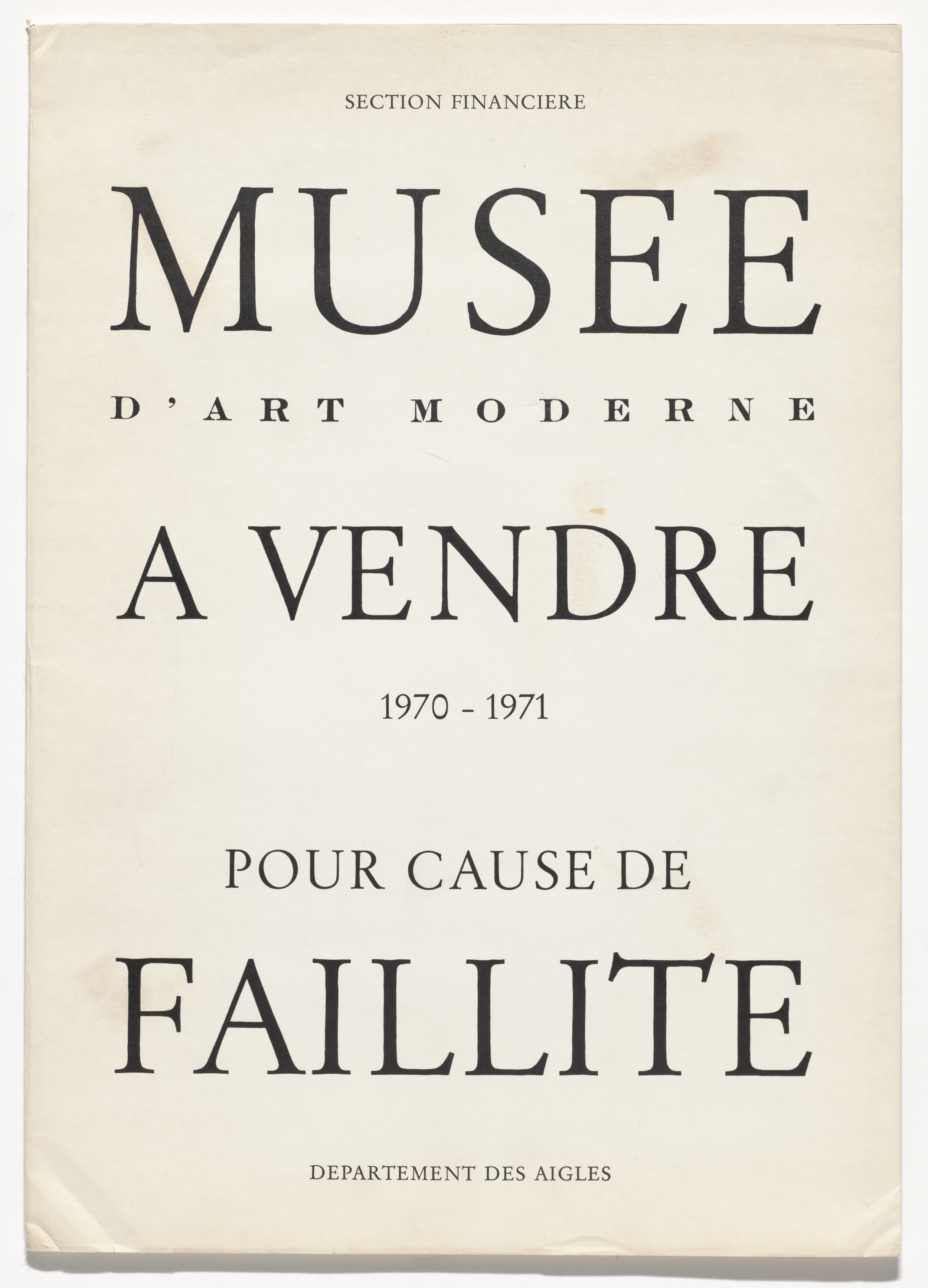

Zeus visits Danae as a shower of gold.

It is Perseus who will ultimately decapitate the Medusa, one of the three hideous Gorgon sisters who turn all who set eyes on them to stone. In Athena’s protectively mirrored shield, he sees that “long yellow fangs hung from their grinning mouths, on their heads grew writhing snakes instead of hair, and their necks were covered with scales of bronze.” From Medusa’s head springs Pegasus, a beautiful white winged horse.

Perseus and Andromeda.

With winged sandals and a cloak of invisibility, Perseus escapes the surviving Gorgons and flies over the coast of Ethiopia, where he sees, “far below, a beautiful maiden chained to a rock by the sea. She was so pale that at first he thought she was a marble statue, but then he saw tears trickling from her eyes.” Andromeda is the daughter of King Cepheus and Queen Cassiopeia, whose vain boast that she was lovelier than Poseidon’s daughters, the Nereids, so inflames the god that he sends a sea monster to ravage the kingdom of Ethiopia. King Cepheus appeases Poseidon with the sacrifice of his only daughter, Andromeda,to the monster, whom she awaits in fright and whom Perseus slays.

This tale of beauty, secrecy, imprisonment by a father, and discovery by a god was a myth I prematurely recognized and would unconsciously live by, and, on charmed occasion, live out. The association of beauty with gold pieces reminds me of a favorite passage from Henry James’ novel The Golden Bowl, the narrator’s description of another forbidden heroine, Charlotte Stant, as metaphorically envisaged by her lover and brother-in-law, the Prince:

He knew above all the extraordinary fineness of her flexible waist, the stem of an expanded flower, which gave her a likeness also to some long loose silk purse, well filled with gold-pieces, but having been passed empty through a finger-ring that held it together.

A second myth I love is the story of Io, a maiden seduced, then changed by Zeus into a beautiful white cow to deceive his jealous wife Hera, who cannily asks Zeus for the cow as a gift, one he cannot refuse. “Hera tied poor Io to a tree and sent her servant Argus to keep watch over her. Argus had a hundred bright eyes placed all over his body...He was Hera’s faithful servant and the best of watchmen, for he never closed more than half of his eyes in sleep at a time.”

To rescue Io, Zeus sends the god Hermes, disguised as a shepherd, to entertain Argus first with his lyre, then with a tale so dull the watchman’s eyes all close and he dies of boredom. Io runs home to her father, the river-god Inachos. “He did not recognize his daughter, and Io could not tell him what had happened, all she could say was, “Mooo!” But when she lifted up her little hoof and scratched her name, “I-O,” in the sand, her father at once understood what had happened, for he knew the ways of Zeus.” Zeus defends himself against Inachos’ revenge by throwing a thunderbolt, parching forever the river-bed Inachos in Arcadia.

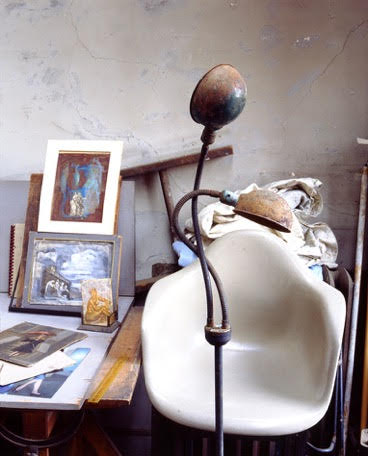

Hera, Argus , and Io.

Hera, in turn, furious that Argus is dead and Io the cow, free, sends a vicious gad-fly to sting her. “To be sure that her faithful servant Argus would never be forgotten, she took his hundred bright eyes and put them on the tail of the peacock, her favorite bird. The eyes could no longer see, but they looked gorgeous, and that went to the peacock’s little head, and made it the vainest of all animals.”

The gadfly chases Io “all the way to the land of Egypt,” where she is worshiped by the Egyptians and becomes an Egyptian goddess. Hera permits Zeus to change Io back into human shape if he promises never to look at her again. “Io lived long as the goddess-queen of Egypt, and the son she bore to Zeus became king after her. Her descendants returned to Greece as great kings and beautiful queens. Poor Io’s sufferings had not been in vain.”

Both these myths are starred with the themes of beauty, jealousy, rescue of a captive (usually through her transformation) and just deserts. I see also the recurrent Oedipal scenario of youth held in captivity by age, spurred by the elder’s fear of being murdered by his offspring, or betrayed by a younger spouse. Demeter’s daughter Persephone is confined to the underworld for half of each year by her husband, Hades; Aphrodite skips out on her old husband, Hephaestus, with the dashing war-god, Ares. Everywhere youth is the prey of parents and gods.

In my late twenties, a psychoanalyst told me that beauty was for me an “overdetermined” category. Primal and primary, perhaps; yet I learned from Athena, my favorite goddess, that wisdom, too, has power. When I read the myth of Paris, Prince of Troy, who must decide which goddess, Hera, Athena, or Aphrodite, should win the golden apple of Discord, Paris gives it to Aphrodite. Aphrodite has promised him Helen of Troy, the most beautiful woman on earth, overwhelming the youth-- himself extraordinarily beautiful--so that he spurns the worldly power offered by Hera and the supreme wisdom pledged by Athena. I told my mother, “I would choose wisdom, because with wisdom you can learn how to have both beauty and power.”

Athena born from the head of Zeus.

Athena springs full-grown from the head of her father, Zeus, as the goddess of wisdom, victory, and, oddly, handicrafts, At thirty I would begin to study this last discipline, as a thread of art history. I identified also with Athena’s precocious maturity, at least in intellectual matters. I loved the gods partly because they were adult, rather than fairytale children led astray. When I was thirty-four, my lover’s mother told me Grimm’s fairy tale, die Sterntaler (star-currency), the story of the little match girl who gives away all her clothes, until, naked in a storm, she is showered with gold coins from Heaven. I silently wept, hiding my face while doing the dishes. When I mentioned the little girl’s similarity to Danae, the mother replied, “Das war aber was anders.” “But that was something different.”

Reading D’Aulaires’ Book of Greek Myths was an imaginative escape that promised an eventual, actual escape from childhood and its tyrannies, the reason, perhaps, that I return to it now as I do not return to Alice in Wonderland, the story of a child. We remain, to one extent or another, sealed in childhood our whole lives long, receiving gold through a hole in the roof, only to be thrown into a sea-chest and swept away: to survive, sometimes to subdue; at last, to love, the mysteriously patterned commotions of our fate.

Theseus, Ariadne and the Minotaur in his labyrinth.

Over the door of the d’Aulaires’ house in Vermont, still lived in by their son, Nils, are inscribed the words, “This is the House that Books built.” The d’Aulaires built for me a house of many mansions, a house with deep porticos, celestial views, looming towers, and hidden doorways. I am still tracing its unending labyrinth.